Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Riches to Rags

Charles is the guy who’s got it all. Born a French nobleman, he decides to be the one aristocrat in France who has a conscience. He leaves his land (and his inheritance) in the dust, sets up shop as a lowly French tutor in London, and begins life over as Charles Darnay.

Despite his attempts to distance himself from the scandals and horrors of the French aristocracy, Charles can’t seem to keep himself out of trouble. The man gets into three (count 'em, three) court cases over the course of the novel. First, he’s tried as a traitor to the English crown. Then he’s tried as a traitor to the French Republic. (Actually, he’s tried as an aristocrat, but at the time, "aristocrat" and "traitor" were pretty synonymous.) As if that weren’t enough, he’s finally re-tried in France—on the same charges!

During in between all those trials, however, he manages to meet and marry Lucie Manette. He even moves into her father’s house in Soho. That’s when he feels obligated to let Doctor Manette in on his secret identity. Of course, Charles doesn’t know that Doctor Manette was falsely imprisoned by Charles’ father and uncle… perhaps it’s better for him that he remains in ignorance.

Nice Guys Finish First

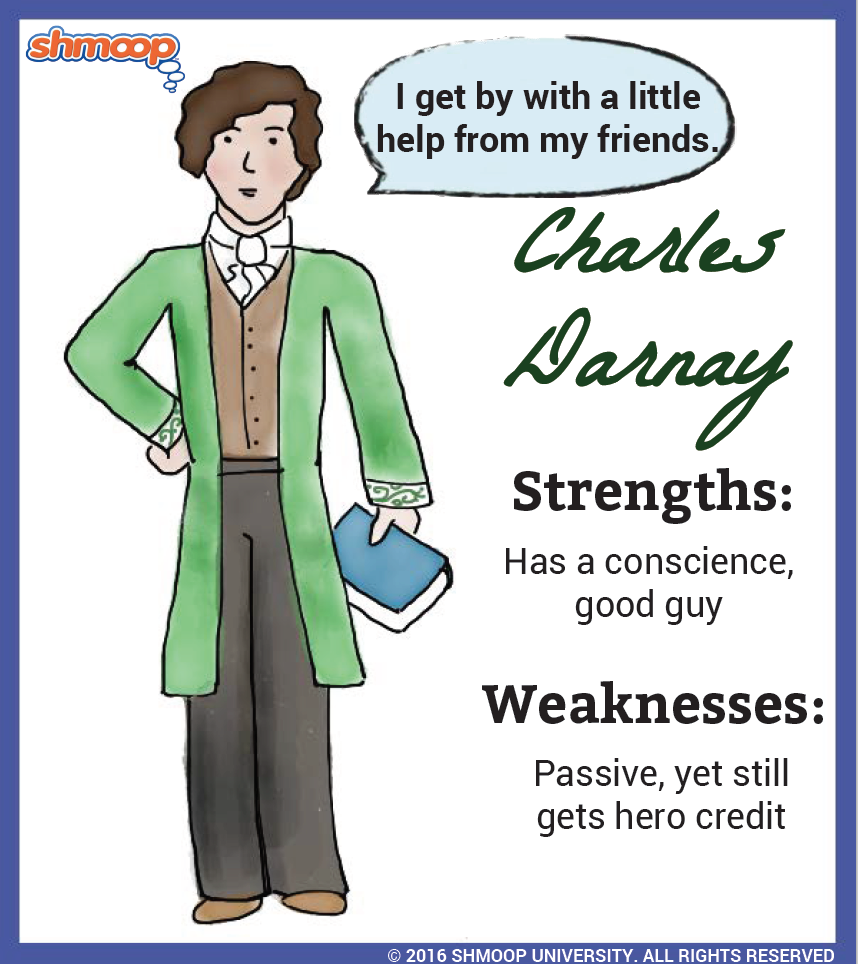

That brings us to a rather interesting part of Charles’ character: even though he seems to be the hero of this little tale, he’s frequently not the man who forces any actions. Sydney Carton gets Charles out of his first trial; Doctor Manette uses his influence to free him in France. And, of course, Sydney changes places with Charles on the night before his execution. For a hero, Charles sure seems to let other people do most of his saving.

Most interestingly, Dickens doesn’t really spend much time developing Charles' character. He’s a good guy. End of story. We do get a bit of moral reflection when Charles decides to head back to France, but it’s only about two paragraphs’ worth of Charles' thoughts. He’s obliged to do his moral duty. Our narrator delves into his thoughts at this moment:

His latent uneasiness had been, that bad aims were being worked out in his own unhappy land by bad instruments, and that he who could not fail to know that he was better than they, was not there, trying to do something to stay bloodshed, and assert the claims of mercy and humanity. (2.24.63)

It’s an honorable set of reflections. Unfortunately, it’s also pretty much the only set of reflections we get from Charles. Most of the time, we’re in other characters’ heads. Even when Charles is arrested and spends several months in La Force, we rarely have an opportunity to experience his emotions.

Perhaps this novelistic distance makes Charles more closely aligned with Sydney Carton than we might first think. Sure, they look alike. But they’re also equally inaccessible to the reader. Charles remains somewhat unimaginable because he’s just so good. Why, then, does Sydney remain a mystery? Perhaps goodness (or even heroism) can come in more than one form.