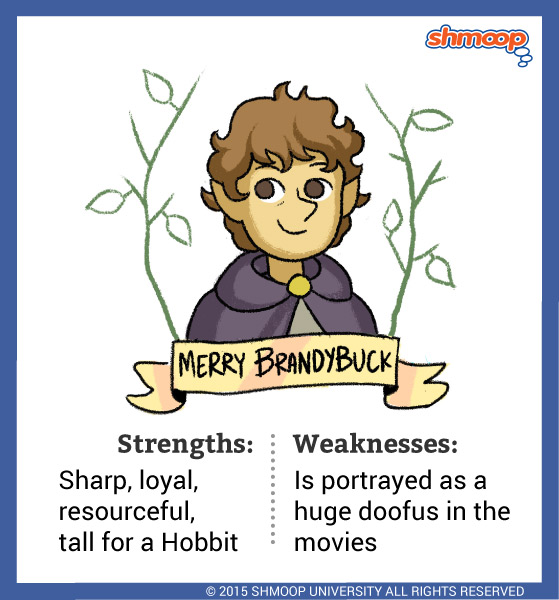

Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Merry and Pippin have pretty minor roles. In fact, they seem to serve mostly as comic relief. (Remember that time when the Fellowship was trying to sneak through the Mines of Moria? And Pippin dropped something down a hole and alerted a whole mine-full of orcs and trolls that the Company was there? That was hilarious.) But then The Two Towers comes along, and these two previously extraneous little hobbits take on bigger and better roles. After all, it's Merry and Pippin who first persuade Treebeard to rally the Ents against Saruman.

And now that we have arrived at The Return of the King, Merry and Pippin become really important. It's in this book that both of these hobbits give us some perspective on the ordinary lives and subplots of the fighting men of Gondor and Rohan. Frodo, Aragorn, and Gandalf are all involved in high-and-mighty deeds. But Merry and Pippin are close enough to the regular Joes around them that, through their eyes, we see a different side of the novel's epic battles.

Take, for example, this quote from Merry when he goes with Théoden as the king's squire and Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas all depart to travel to the Paths of the Dead:

"Good-bye!" said Merry. He could find no more to say. He felt very small, and he was puzzled and depressed by all these gloomy words [about how unlucky the Paths of the Dead are]. More than ever he missed the unquenchable cheerfulness of Pippin. The Riders were ready, and their horses were fidgeting; he wished they would start and get it over. (5.2.66)

Merry is friends with all of these great warriors, and he loves traveling with Théoden. The two have been buddies ever since they first talked over tobacco in the ruins of Isengard in The Two Towers Book 3, Chapter 8. But Merry is not in a position to give the King of Rohan advice or anything like that; he's basically just his assistant. He has no part in the planning of any of these battles against Sauron. After being part of the close-knit fighting force of the Fellowship, Merry now pretty much has to wait for orders and then go where he's told, like any other soldier. Frankly, it's a bit of a let-down.

In our Two Towers learning guide under "Symbols, Imagery, Allegory," we said that we think The Lord of the Rings is an anti-war story. If that's true, then maybe part of that anti-war message is showing the frustrating and dreary parts of fighting along with the exciting bits. Most of war isn't going to be pitched battles against Ringwraiths. There's a lot of sitting around and waiting, especially if you're an ordinary soldier and not an officer. Merry's point of view here shows us a more average, everyday experience of war than we might get from, say, Aragorn's stylish and heroic journey.

Merry and Éowyn: Two Peas in a Pod?

You wouldn't necessarily think it, but it turns out that these two (Merry and Éowyn) have a lot in common. Both want to prove themselves to Théoden. Both resent the idea of getting left behind in Edoras for their own safety. And both have expert training with both weapons and horseback-riding. Oh wait, that last one is just Éowyn—Merry's skills are still pretty much whatever he managed to pick up from the Fellowship before they all split up at the end of Book Two.

When Éowyn goes disguised into battle as "Dernhelm," she brings Merry with her. Merry (being not too bright) does not realize who "Dernhelm" is until he actually sees her fighting with the Lord of the Nazgûl. This fight is central, not only to Éowyn's character, but to Merry's. Because Merry sees Éowyn struggling, and even though he is completely terrified (and even though he can barely stand because of the Nazgûl's "Black Breath"), Merry jumps in and stabs the King of the Nazgûl in the back.

Merry's willingness to fight against evil, even though he is 99.9% certain to die in the attempt, makes him a real hero at last. Back in our The Fellowship of the Ring learning guide, we mentioned that Tolkien has described the purpose of The Lord of the Rings trilogy as "the ennoblement of the ignoble" (source, pg. 220, in a letter to the Houghton Mifflin Co). ("Ennoblement" means to make something nobler and better.) Well, it's the same deal here: Merry starts out as a regular hobbit, but his instincts on the battlefield make him an even greater hobbit than he used to be.

Merry Shows Signs of Character Growth

How do we know that Merry has developed and improved over the series? He basically says so point-blank to Pippin as he's recovering from his battle with the Ringwraith in the Houses of Healing in Minas Tirith:

I can't [live long on the heights]. Not yet, at any rate. But at least, Pippin, we can now see them, and honour them. It is best to love first what you are fitted to love, I suppose: you must start somewhere and have some roots, and the soil of the Shire is deep. Still, there are things deeper and higher; and not a gaffer could tend his garden in what he calls peace but for them, whether he knows about them or not. I am glad that I know about them, a little. (5.8.112)

Merry loves the Shire. That's where he started out in this life, and that's still where his main loyalties lie. But he has seen that there are other (and maybe even greater) things to fight for. When he jumped onto the battlefield to save Éowyn, he was doing it because (a) the Nazgûl are evil, and (b) he could not leave Éowyn to die by herself like that.

In that moment, Merry glimpsed "the heights" of true self-sacrifice and nobility. Now, he's still an ordinary hobbit, so he can't live an ideal existence of extreme moral awesomeness all the time. But Merry knows that there are huge stakes between Good and Evil out there, and even that knowledge has changed him for the better.

We can really see how much these wartime experiences have changed Merry (and Pippin, too) once the hobbits get back to the Shire at the end of the book:

'Lordly' folk called them, meaning nothing but good; for it warmed all hearts to see [Merry and Pippin] go riding by with their mail-shirts so bright and their shields so splendid, laughing and singing songs of far away, and if they were now large and magnificent, they were unchanged otherwise, unless they were indeed more fairspoken and more jovial and full of merriment than ever before. (6.9.35)

The key phrase in this whole passage is "if they were now large and magnificent, they were unchanged otherwise." In other words, both Merry and Pippin learned enough about the great deeds of the world to stand out forever as lords of the Shire once they returned to their own people. But they have also gotten back to the Shire with their essential hobbity qualities intact: they still joke and sing and run around a lot. They are mostly "unchanged." Obviously, this is what separates Merry and Pippin from Frodo, who is all too changed, and who freaks people out as a result. Merry and Pippin learned about the larger world on their travels, but they didn't learn too much to make people uncomfortable.