Character Analysis

Don't Look Now

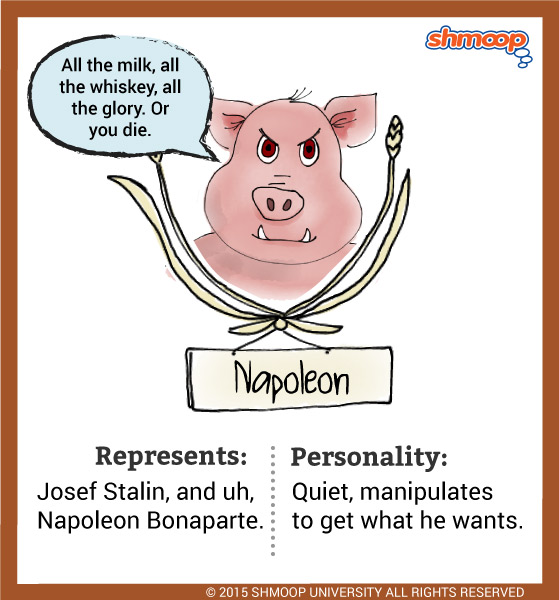

Napoleon is smart—smart enough not to play much a role in the initial rebellion. It's only after the animals have rebelled that he takes a leadership role. When we meet him, we learn that he's "a large, rather fierce-looking Berkshire boar, the only Berkshire on the farm, not much of a talker, but with a reputation for getting his way" (2.2). In other words: Snowball may win Miss Congeniality, but Napoleon wins the crown.

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Not that Napoleon is into democratic elections, or anything. Nope. He operates through cruelty and treachery. Take his little private army: when Napoleon takes nine puppies from their parents and begins raising them himself, no one knows why… until then the dogs suddenly appear, fully grown, to chase Snowball off the farm. What do these dogs do? They "wagged their tails to him in the same way as the other dogs had been used to do to Mr. Jones" (5.15). Napoleon may not have as many ideas as Snowball, but he's got enough of them.

With Snowball gone, Napoleon is the big man on campus. He doesn't need to talk, because he has the aptly named Squealer do his speaking for him. He doesn't need to worry about protests, because he gets rid of public meetings. He doesn't need to worry about sharing power, because he names himself head of every committee. He doesn't need to worry about being popular, because he's got a great PR plan:

In these days Napoleon rarely appeared in public, but spent all his time in the farmhouse, which was guarded at each door by fierce-looking dogs. When he did emerge, it was in a ceremonial manner, with an escort of six dogs who closely surrounded him and growled if anyone came too near. (7.5)

But why doesn't anyone protest? (Well, aside from those dogs, of course.) Well, a lot of the animals are just dumb. It's true. When Napoleon re-writes history to make Snowball into a villain and himself into a revolutionary hero, most of the animals—like Boxer—are gullible enough to believe him. And the ones who don't, like Benjamin the donkey, just can't be bothered to care.

Oh, and there's also the thing where he has a herd of sheep chant loudly whenever anyone questions his version of history.

Socio-Pig

Napoleon's first eyebrow-raising act comes when he unleashes his private dog army on Snowball. The second comes when he squashes the hen rebellion by cutting off their food rations, causing a number of hens to die of starvation.

And then the false confessions start.

What happens is, Napoleon demands that various animals make false, public confessions about how they're traitors or how they used to be in league with Jones. And there's no such thing as forgive-and-forget on Animal Farm: after these false confessions, "the dogs promptly tore their throats out" (7.25). (Well, you have to admit that it's an effective way to get rid of your enemies.)

In this way, Napoleon knocks off his four pig rivals and the hens who acted as ringleaders in the rebellion. It's pretty gruesome:

And so the tale of confessions and executions went on, until there was a pile of corpses lying before Napoleon's feet and the air was heavy with the smell of blood, which had been unknown there since the time of Jones. (7.26)

So, what's this bloody pile of corpses doing in the middle of Orwell's "Fairy Tale"? The whole episode alludes to the 1930s Great Purge, a.k.a. the Great Terror (we'll say). During the Great Purge, Stalin cleaned house. Thoroughly. Some people just disappeared; others were sent to the Gulag prison camps; others had to confess publicly to crimes they'd never committed. Officially, he was getting rid of "counter-revolutionaries"; unofficially, he was getting rid of anyone who disagreed with him. (Check out "Symbols, Imagery, Allegory" for more details on the hen rebellion and Stalin's purges.)

Key fact: Napoleon's preferred method of execution is to have his dogs tear out throats. Aside from being totally brutal and gross, this is Orwell's way of getting in a little extra dig at Stalin. See, Napoleon forces the animals to tell lies about themselves before they die and he makes them afraid to speak the truth—he robs them of free speech. That sounds a lot like tearing out their throats, no?

One thing: dictators often do horribly violent things. That's kind of in their job description. What's bizarre about Stalin is just how horrible his actions were. He seems to have been fueled by paranoia rather than any desire—at all—to work for the good of his country. By making Stalin into a pig, Orwell shows us just how horrific—and absurd—these purges were.

Money or Power? Why Choose!

As soon as Napoleon seizes power, we realize that he has very little interest in Old Major's prophecy. Napoleon doesn't care much if all animals are equal or if they control the means of production, so what keeps him ticking? The same things that motivate most evil dictators: power and greed.

Almost as soon as Napoleon and Snowball seize power, Napoleon starts squirreling away the cows' yummy milk all for himself. And then the pigs start sleeping in the humans' beds. And then they start drinking whiskey and having rowdy parties. By the end of the novel, Napoleon and Squealer wear human clothes and walk around on two legs.

To make sure all of this floats with the other animals, Napoleon keeps shifting the Commandments to make them say what he wants them to say. Squealer explains that the commandment didn't say that you couldn't sleep in a bed, only that you couldn't sleep in a bed with sheets. And it's not that you can't drink alcohol—you just can't drink it to excess. But only if you're a pig. For all the other animals, Napoleon says, "the truest happiness lay in working hard and living frugally" (10.4).

In other words, Napoleon has taken the idea of prosperous living and kept it all for himself. Hmph. Some pig.

Not Just A Pig: Napoleon as Joseph Stalin

If all this is sounding a little familiar, it should: Napoleon is a double for real-life dude Josef Stalin, who served as the General Secretary of the Russian Communist Party from 1922 until his death more than 30 years later. In other words, Stalin was the big man on campus. Er, Russia.

Let's check out some parallels:

Like Napoleon, Stalin was a master at pulling strings behind the scenes. Like Napoleon, he had his own little secret police force, the NKVD (later the KGB). The NKVD assassinated Stalin's rival Leo Trotsky, a.k.a. Snowball, a.k.a. the guy who really was trying to look out for the working class.

Like Napoleon, Stalin kept tight control over the media. Napoleon could take lessons from this guy. He commissioned paintings of himself surrounded by adoring children. He essentially re-wrote Russian history, inserting himself into the Russian Revolution of 1917 and later suggesting that he was solely and personally responsible for winning World War II. And, at the same time he was making himself into Russia's #1 Savior, he wanted to make sure that he was remembered for his modesty.

Lol, Stalin. You kill us.

Like Napoleon, Stalin basically destroyed Russia's economy. Animal Farm's productivity nose dives when Napoleon's in control, so he decides to fill the granaries with sand to hide the smaller harvest. In 1928, Stalin disrupted agricultural production with his Five-Year Plans. When the Plans caused widespread famine across Russia, Stalin covered up the famines to convince people that everyone that A-OK. (See "Symbols, Imagery, Allegory" for more details about this little disaster.)

Like Napoleon, Stalin lived a lavish lifestyle while everyone else was starving. By constantly changing the rules so that he and his friends are exempt, Napoleon totally makes a mockery Old Major's ideas—just like Stalin messed up Karl Marx's ideas. The "worker's state" that actually existed under Stalin was more like a horrible, dark parody of what Marx thought a communist state would be.

In fact, it looked a lot like the exact opposite of communism: fascism.

A Pig By Any Other Name

Some people name their pigs Wilbur and Babe. Other people (ahem, Mr. Jones) apparently name their pigs after monomaniacal dictators.

Napoleon Bonaparte is kind of a big deal. He fought in the French Revolution (1789-1799), and then consolidated power for himself by constructing a French Empire that looked suspiciously like the monarchy that France had just overthrown. (Oh, and then he tried to take over all of Europe in the bonus round.)

When Karl Marx was writing The Communist Manifesto (1848), he was inspired by the ideas at the heart of the French Revolution: liberty, equality, and fraternity. (Liberté, égalité, fraternité, if you're feeling fancy. Or French.) He really believed that communism would create a utopia with all those nice qualities. Unfortunately, no communist state has quite pulled it off—and the French Revolution didn't quite pull it off, either. (There was a little hitch with the guillotine and a lot of nasty executions.)

So, with Napoleon the pig, Orwell seems to be saying something along the lines of, "Hey Marx, didn't you notice how the French Revolution ended?" In other words, Orwell seems to be arguing that idealist thinkers can dream all the dreams they want, but some self-interested pig is always going to come along to ruin it for everyone.

Thanks, Napoleon.

Napoleon (a pig) Timeline